When we interviewed Toradex right before Embedded World 2019, they told us they would focus on their new software offering called Torizon, an easy-to-use industrial Linux Platform, especially targeting customers are coming from the Windows / WinCE environment or who have only experience with application development and are not embedded Linux specialists.

The company has now officially launched Torizon, and provided more details about their industrial open source software solution especially optimized for their NXP i.MX modules.

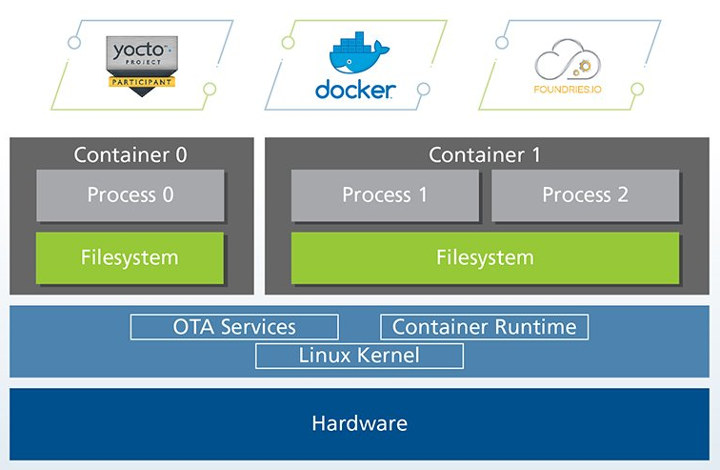

Torizon specifically relies on foundries.io Linux microPlatform which provides full system with a recent stable kernel, a minimal base system built with OpenEmbedded/Yocto, and a runtime to deploy applications and services in Docker containers. The microPlatform is part of TorizonCore (light blue section above) that also includes an OTA client (Aktualizr). TorizonCore is free open-source software, and serves as the base to run software containers.

Torizon specifically relies on foundries.io Linux microPlatform which provides full system with a recent stable kernel, a minimal base system built with OpenEmbedded/Yocto, and a runtime to deploy applications and services in Docker containers. The microPlatform is part of TorizonCore (light blue section above) that also includes an OTA client (Aktualizr). TorizonCore is free open-source software, and serves as the base to run software containers.

To get started, Torizon provides a Debian container including apt package manager that allows developers to easily download and try a large number of deb packages. Toradex will also provide a development tools for pin configuration, display settings, performance monitoring and more, with both local and web-based remote UIs.

One of the tools that should help Windows developers is the Torizon Microsoft Developer Environment that integrates with Visual Studio, making Linux application development and debugging more intuitive for Windows developers. .Net support is also available in Torizon, the company is working on a tighter integration, and is giving away 2x 30 support hours (that must be 60 hours…) to qualified developers moving Windows or Windows CE application to Torizon.

More details can be found in the product page, as well as on Github where you can access the source code and a getting started guide. Note that Torizon is still considered beta software.

Jean-Luc started CNX Software in 2010 as a part-time endeavor, before quitting his job as a software engineering manager, and starting to write daily news, and reviews full time later in 2011.

Support CNX Software! Donate via cryptocurrencies, become a Patron on Patreon, or purchase goods on Amazon or Aliexpress. We also use affiliate links in articles to earn commissions if you make a purchase after clicking on those links.

This seems like cramming as much cool tech into the wrong place as possible. If you are doing OTA updates to a piece of industrial hardware managing hundreds of megabytes of docker images is going to turn the whole thing into a shit show.

(disclaimer: I work for Toradex, but please try to read my answer in an objective way, because I think it contains some valuable technical details)

1. the docker runtime is optional, you can have OTA updates with a Yocto/OE built single image solution. This has still some advantages compared to A/B image approach (less storage, you can have multiple versions on the device, not just last two) and updates are transactional (you reboot to the new image or to the old one, not to something in between).

2. being an old and old-school embedded developer I can understand your concern about containers being “multi-hundred-megabytes bloatware”. If you look a bit better into that topic you will discover that:

– container images are layered, if you only update your own application/service, the distro base layer won’t be touched, so “hundreds of megabytes” shrink down to your app size, as in “traditional” os images.

– depending on the base distribution you choose, you can have a functional base image that is 40MB (debian “slim” variants) down to 5MB (alpine). Still a few megabytes, but definitely not a few hundreds (but we still have to work and trim down our own sample images, I agree).

– multiple images that share the same base layers will use storage space only once for those, reducing the overall storage requirements.

– having multiple separate self-contained environments for different components of your system (ex: “base engine”, GUI, remote HTTPD base administration UI etc.) will allow you to have separate release cycles for each component and not being forced to update a critical component because another one needs a new version of some library that in turn breaks another component… this may not be an issue in your specific scenario, but it’s becoming one for complex systems with a rich feature set.

– you may have multiple versions of your application on the device (provided that you allocate enough storage, of course) and so you can quickly revert to a previous version if something is not working as expected after an update.

– container updates are (again) transactional so if new version was not downloaded correctly, old one is still there, up and running. And if you discover that new version is not working in a specific scenario you may revert back to the working one (this may require some extra storage but, as I already mentioned, not two copies of the same image).

3. feel free to try the “shit show” and provide your feedback, I understand is something very new and may not fit all scenarios (that is not the idea, of course) but not all “cool” technologies are just hype 🙂

>This has still some advantages compared to A/B image approach

It’s not really clear what you’re saying has advantages to be honest.

Anyhow there are numerous advantages to having fixed images i.e. you can sign the whole image and know that the image you are booting is valid and hasn’t been tampered with, you can validate the disk blocks as they are read so you know they haven’t been tempered with while the system is running, the whole thing can be read only,..

>If you look a bit better into that topic you will discover that:

>– container images are layered,

I use docker daily.

>if you only update your own application/service, the distro base layer won’t be touched,

>so “hundreds of megabytes” shrink down to your app size, as in “traditional” os images.

Maybe you haven’t used docker enough to get into situations where dockers cache is broken and you need to flush it to get things to work properly again? 🙂 More on the size thing later..

>– container updates are (again) transactional so if new version was not downloaded correctly,

But now you have two update processes:

– One to manage which containers are running, what versions they are, making sure that containers that are co-dependent don’t break when one of them gets updated but the other fails and so on. Your regression tests now need to account for whatever component that’s being updated to be running along side any version of every other component in the system.

You also have no clear picture how big the whole system could be on disk or in memory. If you update one component and the libraries and other junk it depends on have changed significantly from the base image (the whole point of containers in the first place) that component no longer consumes $application worth of disk space. It’s actually $updated_base_image + $updated_layers + $application. This is where you say “ah but that would only be a small spike, once all the other components are updated they’ll go back to only consuming their delta from the base image”. We know in reality that if you have the potential for every single container to be running almost an entirely different image that it’ll happen.

– Then you have another process to make sure you can update the underlying infrastructure (kernel, docker etc) while making sure its compatible with the containers that need to be running on top of it and not bricking the device. Basically doing the traditional fixed image updates with the added bonus of having tons of different combinations of higher layer components that you have to worry about.

>not all “cool” technologies are just hype ?

Of course not but the majority of them turn out to be just hype.

This is just the “embedded” version of microservices and the “microservices considered harmful” blog posts are already out in full force.

I appreciated the discussion and thank you for the effort you put in replying, I am not a native English speaker, so if some of my replies may not be easy to understand or may sound rude or too ironic, please blame my poor knowledge of the language and not bad attitude.

I like having a discussion with people with different views. As I said, the plan is not to solve any issue or apply to each and every scenario, but I think that this solution has some advantages that you may have to consider when designing an embedded system in 2019, mostly if it’s complex and part of a larger solution involving different technologies.

As usual, is always a matter of evaluating the advantages/drawbacks of the possible approaches and try to choose the best one. Sometimes there’s a clear winner, sometimes it’s more complicated.

Part of the industry moved from firmware to embedded OSs in the 90s, and still have lots of firmware-based solution working perfectly (because OSs can’t fit each an every scenario), I think we will have monolithic and containerized solutions in the future.

You may discard this for your specific needs and this may be a very good choice, but not considering it at all may also be a mistake.

> It’s not really clear what you’re saying has advantages to be honest.

> Anyhow there are numerous advantages to having fixed images i.e. you can sign the whole image and know

> that the image you are booting is valid and hasn’t been tampered with, you can validate the disk blocks as they

> are read so you know they haven’t been tempered with while the system is running, the whole thing can be

> read only,..

So here you are advocating for hundred megabytes images vs granular updates now? 🙂

You can sign individual updates and single files too, and you may have updates coming from different sources (base OS updates from Toradex, app specific updates from you, with you still in control about when OS updates are delivered to devices, of course).

Of course, you can do date with monolithic approach by merging OS updates with your own custom image.

In OSTree system files are read-only by design and the repo is protected, so still security without the overhead of two copies.

I don’t get the point about disk blocks.

You mean loading a single image in memory at boot?

This may not be applicable in every scenario.

Longer boot time, larger RAM requirements are the first things that came to mind.

It may work for a small headless system, may have limits if you have graphic resources or other kinds of heavy content that may be loaded in memory only sporadically and not all at the same time.

But I agree with the fact that it can be a good solution in some scenarios, of course. In this case, you may use only the loader/kernel (building your own version) and forget about the rest. Nothing of the things Torizon adds is getting in the way, preventing you from doing this and at that level, you can still leverage our effort in making kernel compatible with our HW and up-to date.

I am not saying that this is the best solution in each and every possible situation, but signing and secure system can be achieved also with OStree and granular updates, not only with A/B images.

> Maybe you haven’t used docker enough to get into situations where dockers cache is broken and you need to

> flush it to get things to work properly again? ? More on the size thing later..

Cache getting broken on a system where you only run containers, not build them (and probably update them weekly/monthly)? No never experienced that, and I also use docker daily on multiple PCs and devices.

Anyway, even (and only) in this case everything can be fixed with a large download, and having an underlying system still working will allow you to do that.

I can see update scenarios in the traditional approach that can lead to a bricked device with only bootloader working and that may be more complex to recover.

> But now you have two update processes:

> – One to manage which containers are running, what versions they are, making sure that containers that are

> co-dependent don’t break when one of them gets updated but the other fails and so on. Your regression tests

> now need to account for whatever component that’s being updated to be running along side any version of

> every other component in the system.

This is true, updates may have to take into account inter-dependencies.

On the other side, no need to rebuild and ship the whole system if you want to move a button three pixel to the right in the web UI and customer wants it now.

We are also working on good CI/CD integration to automate testing and make the whole process easier to run (but maybe a bit more complex to set up at the beginning, as usual, no free beers for developers… 🙁 ).

> You also have no clear picture how big the whole system could be on disk or in memory. If you update one

> component and the libraries and other junk it depends on have changed significantly from the base image (the

> whole point of containers in the first place) that component no longer consumes $application worth of disk

> space. It’s actually $updated_base_image + $updated_layers + $application. This is where you say “ah but that

> would only be a small spike, once all the other components are updated they’ll go back to only consuming their

> delta from the base image”. We know in reality that if you have the potential for every single container to be

> running almost an entirely different image that it’ll happen.

This is a good point, but manageable.

Also with monolithic image, you can have changes in size after a rebuild and you may have to define a fixed size for the image, making fitting new versions/components more complicated.

Not sharing all libs may also mean that a critical security patch may be quickly applied only to the container exposing the impacted service, not requiring a full system update (testing impact of the changes in the lib affected by the patch on all components/dependencies).

Weight of advantages vs disadvantages will be different in different scenarios.

Managing container images in the right way will add some complexity and overhead, for sure.

But when done correctly it can also give advantages.

Avoiding that you end up with completely different images requires some effort, but it’s not impossible and not the default outcome, I think.

Any advanced technology offers you plenty of chances to shot yourself in the foot 🙂

We are still working on the whole update scenario, but I really appreciate your feedback and considerations.

> Then you have another process to make sure you can update the underlying infrastructure (kernel, docker etc)

> while making sure its compatible with the containers that need to be running on top of it and not bricking the

> device. Basically doing the traditional fixed image updates with the added bonus of having tons of different

> combinations of higher layer components that you have to worry about.

Compatibility between the kernel and upper layers should be manageable, no major breaking changes. You may have some issues that require both a kernel/host OS and a container update, this is true, but it’s not granted that not updating one of the two will lead to a completely broken system.

On the other side, small patches may be delivered quickly and not all system can afford the traditional Xmonths release cycle. Some processes work well with the traditional approach, others with more agile ones.

We also provide Torizon as a Yocto/OE base image, without containers. I clearly see that this could be a good solution for many customers, maybe including you (I am not marketing/sales, so I am not keeping this thread running for my personal revenues 🙂 ).

>>not all “cool” technologies are just hype ?

> Of course not but the majority of them turn out to be just hype.

> This is just the “embedded” version of microservices and the “microservices considered harmful” blog posts

> are already out in full force.

I would agree if we were talking about “blockchain-based artificially intelligent IoT 2.0 OS”, but containers are mature technology in other markets, so I think we are out of the hype phase.

I can tell you that my first reaction to this idea was very close to what I read in your messages, I first played and then worked on this for some months before seeing the potential.

I can understand your point of view, but don’t think that I am here just for the “hype” factor.

New technologies add some tools to your toolbox, it’s up to you to choose if they are right for your job, of course. But keep using a hammer to put screws in, is also not good (even if the hammer has been working quite well for many other purposes).

I’ve been through the whole OS vs firmware discussion in the 90s and I feel some deja-vu.

But as those discussions were anyway interesting and useful at that time, this could be for my future.

>I am not a native English speaker, so if some of my

>replies may not be easy to understand

Your replies are fine. I didn’t get the context linking the two statements. I don’t use English on a daily basis anymore so potentially the issue was on this side.

>I like having a discussion with people with different views.

Same.

>Part of the industry moved from firmware to embedded OSs in the 90s,

>and still have lots of firmware-based solution working perfectly

From my personal perspective: There are hundreds of thousands of devices running something I wrote. The real world consequences of that stuff breaking actually worries me.

If I had to advocate for anything it would be to ban microcontrollers for anything that involves networking while not making devices into basically headless servers that are full of stuff to exploit.

>So here you are advocating for hundred megabytes images vs granular updates now? ?

No. For smaller systems that can fit in the 16-32MB SPI NOR window then full update images are fine unless you are sending them over something like LoRa. For anything bigger sending deltas makes more sense. Of course that gets interesting if you want to compress stuff but it’s not an insurmountable problem. My point is if you have a fixed image you can verify it. You know what it contains. In some cases you know exactly where something is physically located on the flash.

The chances for weird non-deterministic behaviours is minimised.

>You can sign individual updates and single files too, and you may have updates

>coming from different sources (base OS updates from Toradex, app specific

>updates from you, with you still in control about when OS updates are delivered

>to devices, of course).

I can imagine this working but I can also imagine the complexity. With a single signed image you have a single signature (for the image at least). If the signature is correct you know the image is the real deal.

With anything else you have to have multiple signatures. You rely on multiple tools to check that the signatures are right. You don’t know if there is specially crafted data hidden somewhere that the signatures and tools aren’t checking.

>I don’t get the point about disk blocks.

https://source.android.com/security/verifiedboot/dm-verity

With a fixed image you know all of your disk blocks. You can sign all of those blocks and verify those signatures when they are loaded into memory. Say I had SPI NOR connected to my embedded system, my u-boot is signed and the SoC bootloader validates it so it’s trusted, then I have uboot configured to only allow booting of signed FIT images so the kernel and device tree are trusted. What do I do with the rootfs? If I put it in the FIT image it’ll be validated and loaded into memory so I should be able to trust it.. but if I only have 64MB of RAM having it loaded all of the time is a waste. So maybe I use a SquashFS that has a signature I verify in u-boot and only boot and mount if everything checks out. Sounds ideal. I’ve locked everything down so there is no way in via the debug uart, JTAG etc so everything is super duper secure…

3 months later someone does a presentation at DEF CON where they present how they broke the chain of trust by putting an FPGA on the SPI bus and by switching out parts of the SquashFS after the validation has finished rooted the system, grabbed unencrypted versions of everything and found easier remote exploits. With something like dm-verity you could put the block signatures into the FIT so it’s verified by that signature and then you’d be able to validate every block you load while running.

>On the other side, no need to rebuild and ship the whole system if you want

>to move a button three pixel to the right in the web UI and customer wants it now.

Doesn’t that suggest that whatever is creating that UI shouldn’t be in the device itself?

I.e. by exposing a REST API. I think all of the broken web interfaces on server management interfaces, switches, routers etc should have taught us that. 🙂

>We are also working on good CI/CD integration to automate testing and make

>the whole process easier to run (but maybe a bit more complex to set up at

>the beginning, as usual, no free beers for developers… ? ).

That’s good. I can imagine it becoming a lot of work pretty quickly though. Like needing a system that tracks all of the versions of components that are live and automatically generating test units to make sure that there are no version conflicts that developers didn’t think about. Ultimately I think what would happen is each version of a component would be set to depend on the latest version of all of the other components so everything is always updated.

>Also with monolithic image, you can have changes in size after a rebuild and you may have to >define a fixed size for the image, making fitting new versions/components more complicated.

I think that’s true for any way you try to do it. You’ll only have as much storage as the device shipped with so you might end up being in a situation where you need to remain on old versions of stuff because newer versions or the same version compiled with a newer GCC just won’t fit anymore. You can also have situations where new versions won’t run on your hardware anymore. There are a lot of places where loading kernel images bigger than a certain size breaks everything.

If life was simple we wouldn’t have well paying jobs fixing this stuff. 😉

>I would agree if we were talking about “blockchain-based artificially intelligent IoT 2.0 OS”

Haha. I think we probably agree on more than we disagree. 😉

>but containers are mature technology in other markets,

Containers certainly have a place.

>I’ve been through the whole OS vs firmware discussion in the 90s

>and I feel some deja-vu.

I think this is more comparable to efforts like OSGi. I think most people that have used it think the idea sounds great but actually using is like pulling your own teeth out.

> From my personal perspective: There are hundreds of thousands of devices running something I

> wrote. The real world consequences of that stuff breaking actually worries me.

Same thing here. I started working on devices in 1999, both as freelance and employee, and I am still worried that my first customer calls me for an issue 🙂

But on the other side happy to see products I’ve been helping developing used at my local supermarket and lots of other places.

> If I had to advocate for anything it would be to ban microcontrollers for anything that involves

> networking while not making devices into basically headless servers that are full of stuff to

> exploit.

“Everything Should Be Made as Simple as Possible, But Not Simpler”

Sometimes complexity may actually make things simpler to develop and maintain.

You may spend a bit more on HW, but save time. And for small numbers development cost is a high percentage of the overall cost.

Keeping the stuff separated in containers is also a good way to increase security, breaking into one of the services would not immediately allow you to change the whole system.

> I can imagine this working but I can also imagine the complexity. With a single signed image you

> have a single signature (for the image at least). If the signature is correct you know the image is

> the real deal.

> With anything else you have to have multiple signatures. You rely on multiple tools to check that

> the signatures are right. You don’t know if there is specially crafted data hidden somewhere that

> the signatures and tools aren’t checking.

Again is advantages (simple atomic updates, multiple versions available on the device, less storage required) vs issues (complexity for sure, but the whole process can be automated). On the security is true that complex systems are more likely having a bug hidden somewhere, on the other side we tried to rely on widely used components (OSTree, Aktualizr) that are open source, so an issue impacting them has many more changes to be spotted and fixed than on a simpler but proprietary on not widely used solution.

Also the kernel could be simplified, making some assumptions that apply to your specific design, but does this grant that it’s going to be more secure?

With OSTree you can basically choose where to be on the releases timeline, not to apply only part of the changes. And the whole sequence of patches can be controlled.

> Doesn’t that suggest that whatever is creating that UI shouldn’t be in the device itself?

> I.e. by exposing a REST API. I think all of the broken web interfaces on server management

> interfaces, switches, routers etc should have taught us that. ?

True, but some devices may not work with a remote UI, slow connectivity, need of fast reaction times or to show information in real-time etc.

And even cloud-hosted UIs can be broken 🙂

On the other side you may have a container exposing the REST API (only on internal docker network if it does not make sense to access it remotely) and another one hosting the UI. Security issues on the UI side (ex a vulnerability in the framework you used to implement it) won’t lead to full access to the underlying system.

> That’s good. I can imagine it becoming a lot of work pretty quickly though. Like needing a system

> that tracks all of the versions of components that are live and automatically generating test units

> to make sure that there are no version conflicts that developers didn’t think about. Ultimately I

> think what would happen is each version of a component would be set to depend on the latest

> version of all of the other components so everything is always updated.

Of course it would not be reasonable to have a NxM matrix of all the versions, application updates will be delivered in order, also inter-dependencies between containers/services should be manageable. You likely will have N components and 1-2 versions behind the last one.

The goal is to have everything up to date on all devices, but some in between states may grant still usable devices in the meantime. Main difference is that a host OS update will require a reboot, an application update may involve only reloading the container.

> I think this is more comparable to efforts like OSGi. I think most people that have used it think the

> idea sounds great but actually using is like pulling your own teeth out.

Going to see my dentist in 1hr, wil let you know 🙂

Apart from jokes, I can understand your concerns, we really try hard to minimize those pain points, can’t grant that some could be fully removed, but will try my best.

Only time will tell, of course, but today so many devices are running an OS that 20 years ago was met with a lot of skepticism for being too complex to be used on devices.

Unfortunately (or fortunately since, as you already pointed out, it’s what allow us to have a job :)) things are getting more and more complicated.

The internet is not just the very long serial cable some “old school” developers think it is (just replace UART number with a TCP/IP port number), challenges about security and reliability are increasing for devices and what could work 10yrs ago may not work for new projects today.

Torizon now supports OTA firmware update (Alpha release): https://labs.toradex.com/projects/torizon-over-the-air